Introduction:

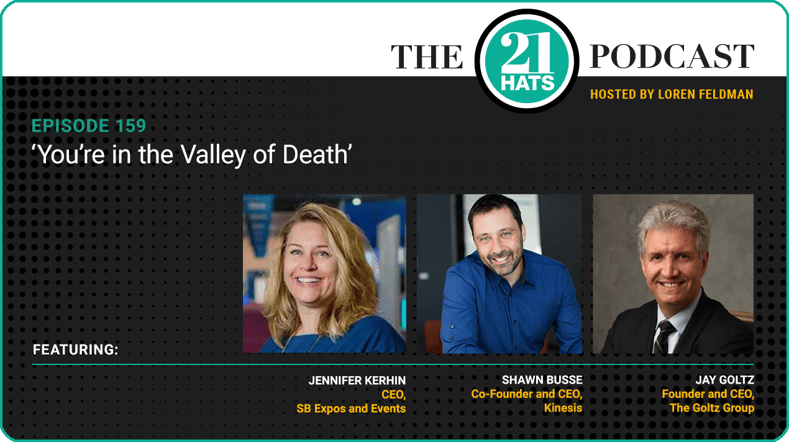

This week, Shawn Busse, Jay Goltz, and Jennifer Kerhin talk about that difficult transition most growing businesses endure when the owner can no longer handle all of the most important tasks herself but also can’t quite afford to hire the people she needs to lighten her load. It’s part of the reason Jennifer, as she’s told us in previous episodes, has been working 12-hour days, six days a week. It’s a challenging transition, and it has a name: It’s the “valley of death,” says Shawn, who compares it to crossing a desert. We also discuss how big the owners want their businesses to get, why important tools and processes seem to break with every $500,000 of revenue growth, and what constitutes the proper care and feeding of salespeople. Plus: Jay has an idea for owners who are having a hard time selling their businesses. The idea involves selling the business to a key employee in a transaction Jay is calling a WE-SOP. Get it? It’s kind of like an ESOP, but it’s a lease-to-own version of an ESOP. A WE-SOP.

— Loren Feldman

This content was produced by 21 Hats.

See Full Show Notes By 21 Hats

Podcast Transcript

Loren Feldman:

Welcome Shawn, Jay, and Jennifer. It’s great to have you all here. I want to start today by picking up on a conversation we had at our event in Chicago. The first thing we did in our peer-group conversation there was to kind of take turns suggesting conversation topics. And then we voted on the ones that we found most intriguing. And the topic that got the most votes and that we spent the most time discussing was one, I think, you suggested, Jennifer, which was: How big do you want to be? Am I right? Was that your suggestion?

Jennifer Kerhin:

It was. And there’s that age-old discussion with business owners, if you look at top-line or bottom-line, right? And so when you think about how big, are you thinking how big your annual revenues should be? Or how much money do you want to take home? And how big is enough?

Loren Feldman:

What prompted you to ask the question? Was there a decision you had to make that was looming that prompted that? Why were you thinking about it?

Jennifer Kerhin:

Our company’s in fast growth, from a revenue standpoint right now. And so I’m spending a lot of time on shoring up operations. Our theme for the year is scalable structure. And so I’m not putting a lot of review on the bottom line, on our profits—not that they’re bad, but I’m not focusing on that. I’m focusing on how to create structure, which takes a little more investment.

And then I started to think, “Well, how much do I invest at this stage?” Because am I investing to create a $10 million company? A $20 million company? Or should I look at it in stages? Should I say, “Okay, I need to invest enough to get $5 million, and then I’m probably having to do another investment to get to $10 million”?

Then someone at that table said something so interesting that I play over and over. They said, “Every half a million dollars in revenue, something breaks in your company operational-wise that you’re gonna have to fix.” And I can’t tell you how many times I think about that. So overall it’s: Where do I put my priorities for the future? And it depends on how big I want to be.

Jay Goltz:

See, I never in all of the—well, not never; now I do—but in the old days, I never thought about how I just kept working to grow and grow. And I didn’t think there was enough. And now, I absolutely believe, at least for me, there is such a thing as enough, which means I don’t need to work any harder. It’s doing just fine. Everything’s good. And I do think it’s a good conversation to have. One of your issues is, you would like to not have to work as hard.

So I would say there is a size of a business that you get to that you can now afford to pay the operations person, the accounting person, and the marketing person. And you don’t have to do the work. And you can’t do that at a $2-$3 million company, usually, because you can’t pay them enough.

So I do think there’s a sweet spot, for lack of another word. And in your case, I don’t know, maybe it’s $8 million bucks, because then you could afford to pay people to do all those things, and you’d be making a lot of money. What’s a lot of money? A 10 percent bottom line? I mean, that’s a lot of money, I think. But I do think it’s worthy of thinking about, especially at your stage.

Loren Feldman:

Shawn, you have the advantage of having had your own experiences, but also seeing inside a lot of the businesses that are your clients’. I’m curious, do you have a sense of what’s more common: Do most business owners kind of just see what happens and grow however much they grow? Or do they think about setting a goal and trying to hit it?

Shawn Busse:

I think I’ve seen both, maybe in equal measure. Although I will say, I am most skeptical when somebody comes to me, and the first thing they say is, “I want to become a $50 million business” Like, if that’s the mission, I find it’s often hard to find motivation around that. And that’s a different thing than what Jay described, which is: I want to grow the business. So I usually see the three camps being: I pick a number, it’s a random number, it’s often a number that people pick because there’s some sort of ego attached to it.

Loren Feldman:

It’s a big round number. For some, it’s $100 million.

Shawn Busse:

Right, so $100 million or a billion. And I usually am not very inspired by that. The second group is probably the Jay group, which is like, “I want to grow because the thing I’m doing I’m excited about. I believe in it. I know it creates opportunities.” And then the third group is just really interested in the work and maybe aren’t that fixated on future state. So it’s really all over the map, Loren.

Jay Goltz:

I knew a guy—he wanted to hit $100 million, and he went bust. I mean, what’s this whole thing with hitting $50 million? The fact of the matter is, most people do not have the wherewithal, the money, the smarts, whatever it is. That’s very difficult, to build a $50 million company. That’s like anyone playing track at the high school going, “I want to be in the Olympics.” Yeah, maybe. But that’s a long shot. But getting to $10 million. Okay. Is that success?

Shawn Busse:

I mean, the statistics are like 4 percent can get to a million, and like 0.4 percent can get to $5 million. So yeah, 10 is actually very, very difficult.

Jay Goltz:

Okay, yeah. And in my case, I was told that less than 1 percent of companies have more than 100 employees. So I’m already in the less-than-1-percent thing. But the point is, the good news is—now, obviously, it depends what business you’re in—but I think if you had a business that was doing, I don’t know, $6, $7, $8 million, you can make a lot of money and have an extremely competent staff that you pay well, so that you can do like me and golf four days a week and go for a massage on the fifth day. [Laughter]

Jennifer Kerhin:

One issue is, yes, to figure out where you want to be personally. But the second part is, where do you invest in your structure to support today, but also tomorrow? So understanding: How much money do you really want to invest? To Jay’s point, my issue is, I need to get some balance back, to take off some of it. How much do I invest in my accounting? Do I hire a controller and a bookkeeper internally? That takes off a lot of effort on me. But that’s a hefty salary to do that. That’s sort of the question I’m going with, is investment.

Jay Goltz:

The hefty salary is you doing your own accounting. That’s a hefty salary. You’re doing the work of somebody who should be making a fraction of what you’re making there. That’s a hefty salary. So that one’s an easy one.

Shawn Busse:

So Jennifer, you’re a professional services business?

Jennifer Kerhin:

Yeah, we are convention management and trade-show sales.

Shawn Busse:

So it’s people-powered.

Jennifer Kerhin:

Yes.

Shawn Busse:

And so you’re at the $3 million mark, somewhere in that range?

Jennifer Kerhin:

Yes.

Shawn Busse:

And I think you said in the last show I was listening to around 30 people?

Jennifer Kerhin:

Yes.

Shawn Busse:

You’re in the valley of death.

Jennifer Kerhin:

I’ve heard that before, Shawn.

Loren Feldman:

What does that mean, Shawn?

Shawn Busse:

So, she’s big enough to where systems matter, and she needs talented people. And she needs to offload the work, like Jay is talking about. But not yet quite big enough—and the next number is probably $4 or 5 million—where it starts to stabilize again. Valley of death is really hard.

Jay Goltz:

And you know what? I have to tell you, that was my life for 5-10 years. When you’re smaller, you can do everything yourself. No problem. I don’t care, you do it all yourself. Then you start to get really busy, and then you get to where you’re starting to get a little overwhelmed. But you can’t go and buy a 10th of an employee. So now you’re overwhelmed for a while. And there’s that period, which I guess you’re calling, whatever you just called it, is going from: I can’t afford somebody but I’m overwhelmed until you finally can get over the hump of, “Okay, now it makes sense.” Yeah, and I absolutely lived through that, and it’s difficult.

Jennifer Kerhin:

My mentor said the same thing. She said the $2 to 5 million for us—

Shawn Busse:

It’s brutal.

Jennifer Kerhin:

It’s the valley of death. She said, “Once you get to $5 million”—she said even maybe four and a half million for me—“life’s gonna change a lot.” But that means I have to put the systems and structure in place now.

Jay Goltz:

Can we change the word from valley of death? That’s not real inspiring. I don’t think you’re gonna die. I think it’s a matter of: It’s the valley of being overworked. But I don’t know that it’s the valley of death.

Shawn Busse:

Here’s why I think it’s an apt metaphor. It kind of goes back to the pioneer days. If you’re going across a desert, you’ve got to have a lot of resources, a lot of water, a lot of food. Because by the time you get to the other side of that desert, you’re about out. And it’s like, if you get halfway and you turn around, that’s pretty deadly too. It’s that between zone, where you have to have a lot of resources. You’ve got to really bulk up. And I think to Jennifer’s point, you’ve got to reinvent all your systems, which costs money. I bet your margins are shrinking like crazy with all this growth.

Jennifer Kerhin:

Yes.

Shawn Busse:

You’re probably in the single-digit realm at this point, and maybe you were in double digits before all the growth. Is that true?

Jennifer Kerhin:

I’m not quite in single digits yet. But it’s a downward number. And I’m prepared for it, because I’m investing in systems and structure to be a $5 million company and to give myself not working six days a week. I like your desert metaphor.

Shawn Busse:

Well, I’ve got more bad news for you. I think your margins are artificial, because you are doing the work of two or three people. And so those salaries are not in your P&L.

Jennifer Kerhin:

Good point.

Shawn Busse:

So your margins are probably… You need more professional people at this point. So that’s the hard part. You’ve got to make those hires.

Jay Goltz:

You’re the woman in the salon who’s cutting the hair of 30-40 people a week. You’re right. You’re a profession to some degree, like he’s saying. But there are some tools here that usually you don’t hear about. One of the tools is, perhaps you just raise your prices 5 percent and put some more margin in there.

Because if you’re growing that fast, and you’ve got the demand, I believe that that is one of the number one mistakes entrepreneurs make, is they don’t charge enough. And that’s always been my number one problem. So that would take the pressure off. All of a sudden, you can go hire somebody now, because you’re going to take in another 150,000 bucks, and it works.

Loren Feldman:

Do you think you could do that, Jennifer?

Jennifer Kerhin:

Yeah, I think so. I think as we get new clients—it’s hard with legacy clients, right? But with new clients, absolutely.

Shawn Busse:

That’s great. I love what Jay said, because I see that over and over. And I made that mistake for many years too, way undercharging. How long have you been at this, Jennifer?

Jennifer Kerhin:

I got my first employee in 2014. But I started, you know, in a basement with a cell phone, in 2009.

Shawn Busse:

Okay, so 14, but it sounds like this growth has been relatively recent. Is that true?

Jennifer Kerhin:

Yeah, in the last 18 months, two years.

Shawn Busse:

I mean, to grow that fast, you should pat yourself on the back. I mean, we’re talking about: valley of death! You’re not hiring enough people! Like, you’re kicking ass. I mean, you’re doing some great stuff.

Jay Goltz:

All right, I’m gonna call it the valley of opportunity, because she’s gonna make some adjustments, and life’s going to get much easier. And she’s going to have better margins. And this is just a time to reboot.

But the beauty is, there is a number out there where you could make more money than you could—I’m not talking about you need to buy a $5 million house in Aspen—but like, reasonably, you can make a lot of money, not be working that hard, and have a manageable amount of people and grief. And I think you can do that at… I don’t know, six, seven, e ight million dollars? And so, there is light at the end of the tunnel.

Loren Feldman:

Jennifer, have you answered your question? Do you know how big you want to be?

Jennifer Kerhin:

I think I’m not going to measure it by numbers. I’m going to measure it by time. For me, it’s working less. I think what Shawn just said opened my eyes. A little aha! epiphany is that my margins are less, if I count the time that really should be other people. That was a little aha! moment. So I think big, small, what I want to get to is where I am taking a few calls a week, like Jay. I like that. And to do that, I have to put people and systems in place and have a healthy profit margin. So less how big, and more of what the structure I need.

Jay Goltz:

I think if you were doing $6 million, and you just did what I call a model income statement and said, “Okay, well, how many people would that be?” I’ve got to think that would work. Now here’s the rub of being an entrepreneur that a lot of people don’t think about: If you’re a lawyer or a doctor or anyone who makes a lot of money, and you make 700 grand a year, you get a paycheck. And you go to your advisor, and you put it in the stock market, whatever. Or you go and buy an expensive whatever. You spend the money.

If you’re a business owner, and you make 600-700 grand a year, the question is: How much of that do you have to leave in the business? And it might be half, and then the money you leave in the business, you’ve still gotta pay income tax on that.

And that is why I’ve never had a lot of cash, because between the taxes and the reinvestment, it just keeps going back in and back in. And it’s okay, because the value of the business is still there. But you have to factor in when you say, “How much money do I want to make?” There’s a difference between how much money you made, quote-unquote, and how much money you took out. There’s definitely a difference in that, because you’re gonna have to keep investing in it.

Shawn Busse:

So Jennifer doesn’t have inventory, but she does have cash flow, like receivables, potentially. Do you get paid upfront, Jennifer? Or do you get paid after you do the work?

Jennifer Kerhin:

I get paid on a monthly basis. One, I love what I do. I love the associations I work with. I love the association world. And the way we get paid is a scope of services divided by 12 for each month. So I have pretty great cash flow.

Shawn Busse:

Nice!

Jay Goltz:

Here’s my concern for you, which is only because I’ve talked to you before, so I know what you’re doing. You’re trying to do this virtually. And I am very concerned that that is going to prove to be very difficult—to continue hiring, training, mentoring, monitoring, managing, leading.

Jennifer Kerhin:

I think for what we do—convention planning and the type of travel and how often we travel—I am not as concerned about that. I think the training part, especially for recent college graduates, is something I’m gonna have to look at. Because when you go fully remote, you need an excellent training program. And we’re not quite there. We have a good one, but it’s not excellent yet. But I’m not worried in the long-term. I can work on that.

Loren Feldman:

Jennifer did also tell us last time that she’s been able to hire quality people who she might not have been able to hire previously, when she was restricted to her particular area.

Jay Goltz:

For sure. It opens up the market to many more people. But I’m just saying, there is going to be the one out of 10 who don’t get their act together. Shawn, when you hire 10 people, how many of them work out?

Shawn Busse:

Before the pandemic, I would say 90 percent.

Jay Goltz:

Wow, that’s excellent.

Shawn Busse:

In the pandemic, and hiring remotely, our failure rate rent went up significantly. It was super depressing. But I think Jennifer is unique, in that—if I understand you correctly Jennifer—your people have to kind of go all over the country. And so you’ve kind of woven into your business model the opportunity to get together. Is that fair?

Jennifer Kerhin:

Absolutely, yes. We’re on show site at least once a month, sometimes three times a month, for these conventions. We’re having dinner, meeting them, deciding when you’re on show site: Who’s great at problem solving. Who’s better at pre-planning and writing that into our systems? Yeah, so it’s a little bit different, because we see each other often throughout the year.

Loren Feldman:

Jennifer, can we go back to what you said before about the notion that every half a million dollars in growth, something breaks? Can you talk about how that’s applied to you?

Jennifer Kerhin:

Sure. So I started thinking about that coming back from that conference in Chicago. And I thought, “Huh, okay, so the first half a million dollars of revenue, great.” But then, what I realized is, we were doing sales using Excel spreadsheets. And that wasn’t working. So then I invested in Salesforce. And then the next half a million dollars, I realized that we didn’t have a good project management system. So as we hired our first staff, we had no way to manage tasks. Then we hired—we’re now on sort of round two—an initial project management software. Then, not even another half a million, but probably $300,000 later, I had used QuickBooks, which was great.

But I had the need to upgrade my systems of how I did it, how my chart of accounts was. So I’m starting to think back, I’m like, “Wow.” And it’s just a product of growth. It’s maybe not so much that it breaks; it’s that what worked for you at that level is not the system that you can take to the next level.

Jay Goltz:

Well, it’s called growing pains. You’re going through growing pains. But here’s the one that you might not have had yet that’s going to be the big one, that’s going to be very troublesome. The person you hired, when you had four people, is maybe going to grow along with you, or maybe they’re going to get peaked out. And you’re either going to have to bring someone in to manage them, which is not going to make them happy, or they’re just gonna get in over their head. Shawn, correct me if I’m wrong—I don’t think there’s a business around that doesn’t outgrow people, and it’s painful. You with me on that, Shawn?

Shawn Busse:

Definitely seen it many times. What’s kind of the average age of your employee, Jennifer?

Jennifer Kerhin:

I would say 35 to 45.

Shawn Busse:

Oh, interesting. Okay. There’s some kind of magic trick in your P&L. Because your ratio of revenue to people is what, maybe $3 million to 30 people? That’s what, $100,000 per employee?

Jay Goltz:

Well, she has no cost of goods sold.

Shawn Busse:

No, but it doesn’t work. Are there part-time people there?

Jennifer Kerhin:

There are. I was about to say, full-time equivalents, we’re looking at 24.

Shawn Busse:

Okay. All right. Thank you. When I first heard that, I’m like, “She’s not making any money, like at full-time.” But that makes sense.

Jennifer Kerhin:

Yeah. And we’re doing about $3.5-3.4 million this year. So you add a little bit more revenue, a little less people. Is it amazing, Shawn? No, but it’s good.

Shawn Busse:

Yeah, that’s $142,000 per person. That’s a ratio I’ve tracked for many years. I think Paul Downs has talked about this. And in the service business, you probably need to be a little higher. What that tells me is, you’re doing too many jobs and maybe not paying yourself a market-based wage.

Jennifer Kerhin:

I think, too, my problem is fine-tuning scope a little bit better to ensure that we’re getting paid adequately for the scope of work we’re doing.

Shawn Busse:

Oh, yeah. Okay.

Loren Feldman:

So Jennifer, are you going to start raising your prices?

Jennifer Kerhin:

It’s minimizing scope, to be honest. I think it’s less about prices. It’s more of, I think our prices per hour or okay. It’s the, “Hey, I thought this would take 10 hours and it took 50.” That’s where I have to focus more energy.

Jay Goltz:

Well, that’s one problem. The other one, I’m going to guess, is you’re going to figure out if you haven’t already that some customers you just can’t make money on. Period. End of the story. They just require more tension, more time, more than they’re willing to pay. And it’s part of life. Sometimes, you just have to lose them. I don’t do it a lot. I almost never do it. But there have certainly been cases where we’ve just realized this just isn’t worth all the trouble. You got any of those?

Jennifer Kerhin:

I used to. I don’t think anymore. I think I got a lot better at that, Jay, of realizing from a time standpoint. Our scope issue isn’t really client-based. Our clients now are wonderful. Our issue is more the technology needed. It’s, “We thought it would only take 10 hours.” And what we’re realizing is, “This was way more complicated from a technical standpoint, and we need 50 hours.” And that’s me not understanding this post-COVID world of doing virtual and hybrid events.

Shawn Busse:

Oh, right, it’s more complicated.

Jennifer Kerhin:

It’s way more complicated. This is something that nobody knows how to do. It got created two years ago. We’re all still learning. That’s the problem, I’m saying. Our clients are fantastic. It’s that the technology is brand new.

Jay Goltz:

See, that’s actually an opportunity, because you’re smart, and you’re gonna figure it out better than other people do. And that’s why you’ve been able to grow the business, because you’re better at figuring this stuff out. People who have been doing the same thing for the last 30 years might not be as apt to be able to navigate it. Maybe they’re just gonna retire.

Read Full Podcast Transcript Here

.png)