Introduction:

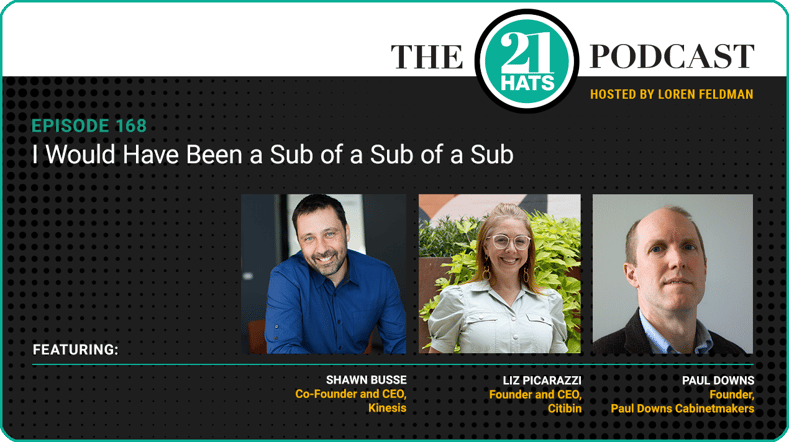

This week, Shawn Busse, Paul Downs, and Liz Picarazzi talk about when it makes sense to walk away from a client. Liz, for example, is tired of dealing with bureaucracy and being at the bottom of the food chain. In one instance, she was so turned off that she actually recommended a competitor for a job she no longer wanted. Paul has a simple test: If it’s easy work for a bad client, okay, fine. But if it’s hard work for a bad client, “Just don’t do it.” Of course, there are times in the life cycle of most businesses when that’s easier said than done, when you have to accept almost any work offered. Those are the tough ones. Plus: Is it time for business owners to take artificial intelligence seriously? And should owners care that a well-known economics firm is predicting a depression in 2030?

— Loren Feldman

This content was produced by 21 Hats.

See Full Show Notes By 21 Hats

Podcast Transcript

Loren Feldman:

Welcome Shawn, Paul, and Liz. It’s great to have you here. We spend a lot of time talking about marketing and generating revenue. Today, we’re going to talk a little about turning work down, saying no to potential revenue. Liz, I gather you’ve done this recently. Can you tell us about it?

Liz Picarazzi:

Sure. So I’ve had a couple of instances this year that, if they had happened last year, I would have been really frustrated that the deals didn’t go through. But because these deals didn’t work out this year, I am feeling really relieved—like I dodged a couple of bullets. And in one instance, it was sort of like a city project that had come up as a potential 2021 range. And it was one of these things where I would have been a sub of a sub, and maybe even a sub of a sub of a sub. And the distance between me and the decision maker was so long that the thing took a really long time. And there was a lot of confusion.

And it was the government. It’s due to bureaucracy. But when we reached the end of it, we had put in our bid a couple of years earlier. And at the time, it was for two-thirds of what was in the RFP, and we were very clear: “This one-third, we’re not going to handle. You’re going to need to find another vendor for it.” They went off. They couldn’t find a vendor for it. They came back to us and wanted us to do all of this new-product development to develop something for them. And we basically said, “No. We haven’t been paid a dime. We’ve been on phone calls with you for over two years. You’ve had these teams just change, the people involved, a different cast of characters.”

So I don’t want to say they broke up with us or I broke up with them, but I think it was mutually understood that it wasn’t a good fit. And it was so much of not a good fit that I even recommended a competitor to them, because I knew the competitor could offer that one-third that I couldn’t. And that actually was kind of the end of it, because the other competitor also happened to have the other two-thirds of the stuff. But it was a lot of time. It was very frustrating. And I think what’s notable about it is that starting from such incredible excitement—“Wow, this would land us into this new city agency that we would be able to scale across this huge portfolio,” down to, at the end, actually recommending a competitor. Who in the world would have thought that would have happened when it first started up two years ago?

So another recent example, especially in the last couple of months, is we’ve gotten a lot of requests for a different type of trash container, which I have thought that we might want to get into. But when they come in, I realize that we have so many other products that we’re really busy with. We actually have three product launchings—which I haven’t even talked about here—that I don’t want to get distracted from. And so I can feel more confident to walk away. A couple of them are intriguing, and I’ll kind of keep it in the background as something in the future we might want to do. But anything with the government, where there are multiple layers between us and the decision maker, we’ve decided to stay away from, because it can really suck up the time.

You know, if there’s a change in the guard, or change in administrations, the work that you’ve been doing can be essentially canceled. And it’s just the cost of servicing and the cost of acquiring certain customers that end up to be high maintenance. The problem is that you don’t know if they’re going to be high maintenance to begin with. And we’re kind of looking as we move forward for any sort of indicators that they’re going to be a pain in the ass.

Shawn Busse:

Liz, is this a design issue? Meaning, folks are asking you to design solutions as part of an RFP, and that takes work and communication? Or is this a workflow issue? Meaning that you’re selling to somebody who’s selling to somebody who’s selling to somebody? Or is it both of those issues?

Liz Picarazzi:

It’s actually both.

Shawn Busse:

Okay, it’s a double whammy.

Liz Picarazzi:

Yeah, it’s a double whammy.

Shawn Busse:

Yeah. So what I hear you saying is, you want to get out of selling to people who are selling to people who are selling to people. So that’s one piece. And then the other piece around folks asking you to do design services in order to get a job: Are you still going to do that? Or will you do that if it’s selling directly to the end buyer?

Liz Picarazzi:

I mean, a lot of our design services over time have come from customer requests, and almost like a prototyping relationship where we’re ideating with them, and we’re coming up with a solution. That’s how we came up with our package locker, our mailbox. We just launched composting, actually, yesterday in Boston. And that’s something where they essentially fund the development. So if we’re taking like 80 percent of existing product, and we’re developing a new module for them, they’ll essentially be paying not a design fee, per se, but the cost per unit is a lot higher because they’re more like one-offs.

Shawn Busse:

Did they agree to buy it in advance? Or is it speculative?

Liz Picarazzi:

They buy it. Yeah, they do agree to buy it in advance. But with one of them, it would have been incredibly speculative. And it was weirdly speculative while we knew that a competitor had exactly what they wanted. So then we thought, “Well, why would we put our funds toward developing this if we don’t know that we could definitely develop something that’s better than that competitor?” When in many other areas, we dominate, and we’re better than that competitor. Why try to get into their space?

Paul Downs:

Well, there are reasons. If the competitor has a product that on paper looks good, but everything else about that company is a disaster, then you have the opportunity to eat their lunch. Because product development is an indication, really, of customer service. You have to be communicating back and forth with the client. And you have the opportunity to demonstrate the intangibles of working with you. I guess they’re fairly tangible, but they’re not just the product. And that can be a real distinguishing element when you’re working with clients.

We’re doing this every day. That’s what we do. We get all kinds of requests from people, and we have to decide whether they’re any good or not. Well, I would say 100 percent of the time, the people who approach us have easy-to-access, cheaper alternatives. And so if you’re going to be working, developing new products, you’ve got to sort of make it a thing you do and not just be scrambling. Now, I don’t think you intend to become a custom maker, because your manufacturing is actually in China. And I don’t know how you handle that when you just need one of something. But you know, it’s just like a business decision about: First, do we want to deal with these people? Second, are we the kind of company that can do that?

Now, if you’ve got 15 inquiries for a composting bin, that’s an indication people need composting bins. But if you tailor your solution to any one of those people, you may not really be making the market-acceptable product. You may be too custom to roll out for the whole world. So, again, a decision: I’m hearing people want this. They’re calling me for it. Do I want to just create the offering that I think is the best fit for the largest number, or actually become a custom manufacturer? And if you don’t have in-house manufacturing, it’s really hard to be a custom manufacturer.

Shawn Busse:

Paul, in terms of your process, somebody comes in and says, “Hey, I’m an architect developing this floor plan for this big fancy corporation, and we need a giant conference table.” There’s a design element to that. Do you do that as part of your discovery process? Do you charge for that? How does that work in your business?

Paul Downs:

We do it for free. And we do a lot of work for free. Because as I said, we’re never the cheap alternative, and we’re never the fast alternative. So what we have to do is show right from the get go that we’re the best alternative. And that means that my particular selling process is about giving away a design, more or less. But what’s more interesting is the process. We had to set up a process by which we can produce designs, and we do that all the time. So we’re good at it.

But the process by which you share the designs is really customized. And a lot of what we will give away or not give away or show or not show really depends on the configuration of the client and what they’re likely to do if we just handed them, “Hey, here’s some ideas.” And so with some clients, you just give them the whole package. “Here it is. Say yes or no.” And that’s usually when you’re dealing with a decision maker directly. And then with some other clients where you’re dealing with, say, a mid-level corporate buyer, you don’t want to do that. You want to show them that you can solve the problem. But you don’t want to give them the stuff, because they’ll just take it and send it to somebody else for pricing. And so we have to decide—

Loren Feldman 13:22

What’s the difference there, Paul? What do you show, if you don’t want to give it all away?

Paul Downs:

Well, it’s not necessarily what you show. It’s how you show it. So we have ways of showing things that don’t end up with an easily shareable file in the client’s hands. And that’s usually doing a screen share, showing them animations, giving them the whole pitch, but not giving them the files. And then in other situations, like suppose we’re dealing with an executive assistant to the CEO of a billion-dollar corporation. We will give that person everything, because what we find is that the CEO is not going to be looking at any of this during his or her workday. And so we want to give it to them in a format where, at four in the morning when they’ve done everything else, they’re like, “Oh, yeah, I gotta look at the table.” It’s just there for them, everything.

And so we’ve learned through hard experience just how to analyze: Who are we dealing with? And exactly how do we want to share? Do we want to do a complete, like, “Here it is”? Or a slow striptease? Or, whatever. There are a lot of different ways to do it. And it really depends on the buyer.

And we learned a lot of this from sales training, which is to not just give away complete solutions, but to think carefully about when you might want to do that and when you might not want to do that. Once we started being more discriminatory, our sales doubled, because we weren’t just handing it away. You know, we weren’t doing free consulting, is how we used to call it.

Loren Feldman:

And you attribute that doubling of sales specifically to that issue?

Paul Downs:

Yeah.

Loren Feldman:

Wow.

Paul Downs:

I mean, it’s really about understanding who you’re dealing with. Again, this is as a custom manufacturer. So if we customize the product, why wouldn’t we customize the process? Now for Liz, she’s in a different business. She’s trying to amass orders—large orders, or multiple orders—for one thing, and then send them off to another continent for manufacturing. And that’s not nearly as flexible as I can be, but it delivers product at a much lower price than I can. So I would say her problem is more about just identifying whether she wants to work with someone or not, just like a yes or no decision.

Liz Picarazzi:

Yeah, I was just gonna say that I actually am often able to prototype really fast with my factory—like, surprisingly fast. Try this lock, try this handle, let’s try it this way. Can we have a smaller gauge? And I can sometimes get things within two weeks.

Paul Downs:

In your hands? That’s amazing.

Liz Picarazzi:

Yes, yep.

Paul Downs:

And they just fly it over? How do they get it over?

Liz Picarazzi:

We airship them over. We go and pick them up at JFK. A number of new product launches and components that we’re doing in the next month, that’s how we develop them. And then we usually have a small production run before we go into tooling and do mass production. But especially with some of the city work we were doing where we were iterating and improving, we were able to do rapid prototyping in a way that I think people like you would never have imagined.

Paul Downs:

Yeah, I didn’t imagine it. Well, that’s amazing.

Liz Picarazzi:

We have a great factory, and we’ve been with them for six years. They know what we want. Things just… they work.

Paul Downs:

All right, I take it all back. [Laughter]

Shawn Busse:

Well, you know what, Paul’s a value shop. So essentially, he creates custom solutions and solves problems for customers. And Liz is more of a value chain, meaning she’s connecting together complex things and supply chains to create value. But what you might be getting into, Liz, is more into the world of the value shop, which is where if you start to solve problems for municipalities in unique ways and you build a skill-set around that, it’s really interesting. Because I think there can be much higher margin and much more difficulty in comparing price, if you add that as a component. If you think about businesses that have those components, they can manufacture, but they can also do custom solutions. Sometimes you can build good complements to one another.

Liz Picarazzi:

Yep. And that’s really the direction that we’ve gone in, because we already had the modularity with the size of the trash enclosures. But then we started adding on different modules, and that was based on requests. And they were fairly easy. And part of it is because, fundamentally, we are a modular product. We very rarely—although, I have to take it back. For Boston, we did develop a totally different-sized cabinet. But it was a modification on what we already had of several components. And we were able to meet their needs without having to develop a whole new product.

Loren Feldman:

Liz, there was a lot in what you initially told us. I’m curious about a couple of things. One, you mentioned this discrepancy that you had with the government entity, where you thought you had submitted a bid for two thirds of the project, and they thought you submitted a bid for the whole thing. Can you tell us more about what that third was, and how that happened?

Liz Picarazzi:

Right, so the first two-thirds were a product that we already have that was just a little bit enhanced. The third that we didn’t, it was essentially parking for trash carts. So it’s sort of like one- to three-yard carts, that oftentimes large housing uses—other buildings, schools, and whatnot. They essentially wanted a shelter or parking for that. And that is something that—

Loren Feldman:

They wanted you to build this?

Liz Picarazzi:

Yeah, they wanted us to build that. They gave us the schematics. And if I knew I would have a P.O., I would have done it. But it felt very speculative, and this sort of not realizing for over a year that they didn’t have a third of what they needed, like why did it take them so long to figure that out? Did the client even have an idea that they misunderstood my quote? That was the part that really bothered me. I felt like it was kind of thrown under the bus and that the customer—who I would someday like to have as a customer—is now potentially thinking like, “Oh, Citibin, they were weird with the quoting. Or they had confusing quoting.” It’s like, “Well, no. You had a 24-year-old over there translating the information.” And it was a very slow contract as well.

And then overall, I’ll just say, I don’t like the idea of these huge contractors that have gigantic contracts with the city that are allowed to just not move. Like, they just sit there. And then when they move, they want you to move fast. And I had this feeling of, I realized we were going to be miserable. Like, as a team, we were already so confused that we thought, “Well, this is just not going to work out.” So I don’t know if that answered your question, but I’m glad. I may sound disappointed. I guess what I’m disappointed about is that it took so long to figure that out.

Shawn Busse:

Yeah, you wasted time you can’t get back.

Paul Downs:

Again, this is a problem we have to deal with all the time. We have in our mind a pretty clear picture of different types of clients and different configurations of deals. And some of them are good, and some of them are bad. And anytime you’re working as a sub, it’s already bad. But if you’re working as a sub of a sub, it’s bad squared. And if you’re working as a sub of a sub of a sub, it’s bad times 10, or whatever. [Laughter]

Liz Picarazzi:

Yes.

Loren Feldman:

We’ll have to check the math after the show.

Paul Downs:

To the power of 10. How about that?

Liz Picarazzi:

Exponential bad.

Paul Downs:

It’s exponential bad, double plus on bad. So you’re just like: Okay, if that’s how we have to work, it might be better to just say no, or explain why you’re saying no, right from the get go. Because our thing is, we always do way better if we can get in touch with the final buyer. But frequently, we’re working through an architect and a furniture dealer. And so if they want to keep us at arm’s length from the final person, it’s like, “Okay, you can do that. But this will all go better for everybody—we promise you—if we can just talk to the final person,” and that’s the person who signs the check. That’s your client. Why wouldn’t you want them to be happy?

And they either accept that argument or they don’t, but if they don’t, then we’re often like, “You know what? Bye. To hell with you. We don’t need you.” We’ve got other things to do that are more likely to work, because what you’re looking for all the way along are signs that they’re willing to participate in the process that you’ve set up—not necessarily that they’re going to try to force you into the process that’s convenient for them.

And I’m not even sure we can describe this on a podcast, but if you think of a Cartesian coordinate set with a vertical axis and a horizontal axis, the vertical axis starts at the top with a good client who does what you want to do. And at the bottom, it’s a bad client who’s maybe a jerk or just won’t participate in your process. And then on the right hand, on the x axis, you have easy work. And on the left hand, you have difficult work. And what you want to do is stay out of that lower left quadrant where you’re doing hard stuff for bad clients. And it sounds like in your first example you brought us, that’s hard stuff for bad clients. Just don’t do it.

Now, you can do easy stuff for bad clients with the understanding they’re gonna be bad clients, but at least what they’re asking you to do is falling off a log. And you can charge them extra for being jerks or not. And then the other two quadrants are more like, yeah, you want to do easy work for good clients. That’s a no-brainer. Doing hard work for good clients depends on the particulars. But that’s a very easy matrix to think about clients and work. And what do you want to do? And what do you not want to do?

Liz Picarazzi:

Yeah. Well, the other thing is looking at the team, and how are they going to be if they’re put in a place where it’s bad clients, bad pay, all of it? That’s really discouraging. And I’ve got some great employees who I would have deployed who then wouldn’t be working on the great profit-making projects that they’re now doing. So I was kind of fast forwarding to this being thrown under the bus. Imagine being thrown under the bus and losing money on it. That’s a major kick in the balls.

Paul Downs:

Hard work and bad clients make for bad situations: bad work, unprofitable, ties up your team, leaves them discouraged, and exposes them to abuse from people who are horrible. Like, why would you do that? It’s much easier to just walk away from that. When you first start a business and you’re desperate for any kind of client, you end up doing that kind of work. Or if things are tough, and you just need to get dollars in the door, you may end up doing that work. But at least you’ll have some idea of where you’re heading, which is trouble all the way through.

Loren Feldman:

So Liz, it occurs to me that this is at least tangentially similar to issues you’ve raised previously about, I guess, really the focus of your business. Should you focus on where you’ve had the most success, with trash enclosures? Or should you try to expand and do other things? Should you do bear-proof enclosures for different markets? Should you expand geographically, even though there’s lots of opportunity in your hometown of New York City? Do you see these issues as being related?

Liz Picarazzi:

I do. And we’re actually already doing all of the above. Against the advice of many on 21 Hats, we are moving ahead with our bear-proof enclosure. [Laughter] We’re doing the test in Montana.

Loren Feldman:

You sound proud of that, Liz.

Liz Picarazzi:

You know, I’m looking forward to it. Montana, late September, the bears are going to be attacking the bin. This is a new bear-proof version of the bin. And we’ve already actually started selling, even before getting our certification. So I’m looking forward to the marketing on that. I’m laser focused on that. I don’t want to work on the stupid government stuff with wasted time on meetings, when I can be working on my bear marketing, and the bear video that I have planned, and hopefully the viral videos and stuff that really lights me up. So that’s happening, as well as nationwide expansion.

So we’re going to a conference in October called the International Downtown Association. And it’s basically downtown areas for all major cities, business improvement districts. The same sort of customer base that we have here in New York, now we’re going to be working in other cities. So we have some work moving ahead with those.

So yeah, we’ve got other things in the pipeline and definitely a lot to focus on and stuff that I think will be really profitable, eventually. But the marketing for the bear-proof is going to be a lot different, and it’s going to be very regionally based. Like even though we have bears in the Northeast, I’m not going to be targeting the Northeast with the marketing. We’re going to be focusing more in the mountain regions, resorts, homeowners associations.

Read Full Podcast Transcript Here

.png)